Ocular melanocytic neoplasia is quite common in small animals. Here is a quick guide to help you figure out which ones are SCARY and which ones are no big deal.

Eyelid:

As we all know, eyelid tumors are very common in dogs, less common in cats. Melanocytic tumors account for nearly 20% of reported eyelid neoplasms and most (62-87%) are reportedly benign but some (13-38%) are malignant.

Eyelid melanocytic neoplasms can be pedunculated and focal or can be infiltrative with a more diffuse involvement of the eyelid margin.

Surgical removal is typically recommended if the masses are small and focal however if there are multiple, more diffuse masses affecting a larger surface area of the eyelid margin, this can be tricky. Cryotherapy alone or in conjunction with surgery has been effective in treating benign melanocytic lesions. Distant metastasis is rare for both malignant melanomas and benign melanocytomas.

Feline eyelid melanocytic tumors are very rare (2-8% of reported eyelid tumors). Treatment with surgical excision is typically recommended. In general eyelid melanomas follow a more benign course but local reoccurrence and distant metastasis may occur.

Typically, no big deal!

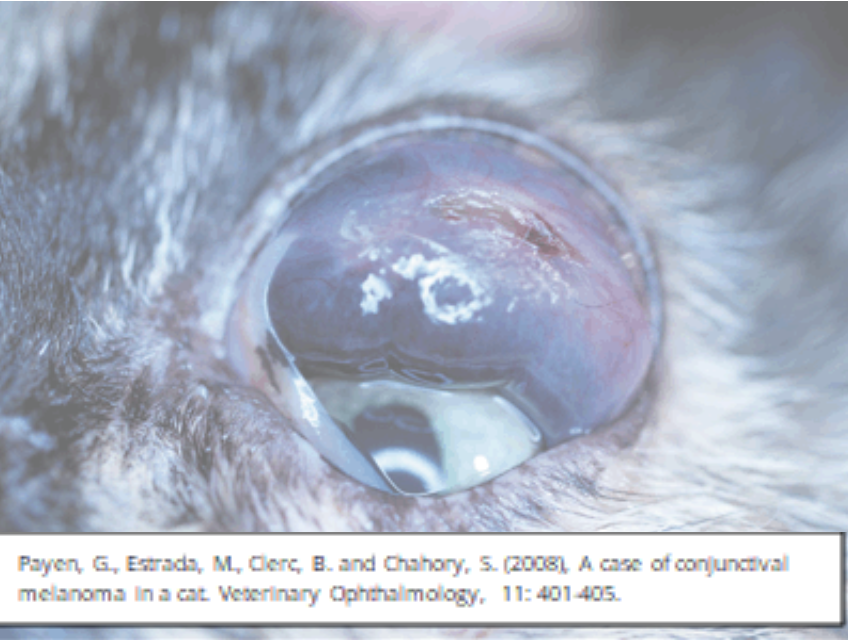

Conjunctival:

Conjunctival melanomas occur rather infrequently in dogs and cats but can arise from any part of the conjunctiva with the third eyelid being the most common location. Weimaraners may be predisposed, and these tumors tend to be quite locally invasive. The metastatic rate for conjunctival melanomas is higher than another other melanocytic ocular neoplasia in domestic species.

Most conjunctival melanomas are darkly pigmented however amelanotic melanomas affecting the conjunctiva have been reported. Wide surgical excision with possible adjunctive cryotherapy is the treatment of choice. Depending on the size of the mass, and in cats due to the more aggressive nature of the disease in feline patients, enucleation or exenteration may be recommended.

Consider these melanomas to be sort of SCARY.

Feline Conjunctival Melanoma

Limbal (Epibulbar):

Limbal melanomas in both dogs and cats are generally considered to be benign tumors. They are the most common ocular melanoma in canines accounting for 20-50% of ocular melanomas in dogs. German Shepherds and Retrievers appear to be predisposed.

These tumors arise from the limbal cells. They classically present as raised, smooth, brown to black heavily pigmented subconjunctival masses protruding from the surface of the eye at the limbus. The abnormal pigment may extend within the adjacent cornea and sclera and rarely may extend intraocularly. Limbal melanomas have never been reported to metastasize in dogs, however tumor reoccurrence is common after surgical removal. Distant metastasis has been reported in cats, but most feline limbal melanomas are benign (like canine limbal melanomas) and metastasis is rare.

A biphasic presentation has been reported in young (<4y) dogs and older dogs with younger dogs tending to have rapidly growing, more invasive tumors. Older dogs tend to have a slower progression with a lesser chance of intraocular invasion.

Surgical excision with either partial or full thickness keratectomy/sclerectomy is usually recommended. Adjunctive treatment with cryotherapy, strontium irradiation, Nd:YAG, or diode laser therapy may be helpful at preventing regrowth. In some cases, full thickness en-bloc excision or deep keratectomy/sclerectomy may require reconstruction of the globe with donor material, conjunctival or biosynthetic grafting. With extensive globe involvement, surgical removal of the eye may be necessary.

These are usually no big deal.

Uveal:

Uveal melanocytic tumors are among the most common primary intraocular tumors in dogs and cats. Most uveal melanocytic tumors arise from the iris or ciliary body but can also arise from the choroid. The clinical appearance and biological behavior are quite different between the two species.

In dogs, uveal melanocytic neoplasms are predominantly benign melanocytomas. However, malignant melanomas are not uncommon. In canine patients, the mass is often focal/solitary, heavily pigmented, and forms a true mass within the uveal tissue. These masses may alternatively cause diffuse iris thickening and hyperpigmentation. Dyscoria, secondary glaucoma, uveitis, and extension through the sclera may also be noted in clinical presentation.

Choroidal melanomas are much less common, representing ~4% of ocular melanocytic tumors, and may be an incidental finding on retinal examination. They may cause local inflammation or retinal detachment and can lead to secondary glaucoma. Extension through the sclera into the orbital tissues may occur later in the disease process. Distant metastasis has been reported; however, these tend to behave rather benignly like the other uveal melanomas arising from the iris and ciliary body.

Histopathologic criteria are necessary to differentiate between benign melanocytomas and malignant melanomas. The size of the tumor, mitotic index, and invasion of the sclera are not predictive of survival. Even with malignant uveal melanoma, distant metastasis is uncommon. However, survival between the two groups (benign versus malignant) has been reported to be statistically significantly different. Despite the low rate of metastasis, it is worth pointing out that dogs with malignant melanoma have a statically shorter survival time compared to dogs with benign melanocytomas.

Enucleation is typically recommended when a uveal melanocytic neoplasm is noted. Biopsy of the iris tissue or iridectomy may be performed to obtain a diagnosis; however, with this invasive sampling, there is a risk of hyphema. The use of diode laser to treat focal melanocytic neoplasms is becoming more popular but controversial due to the risk of distant metastasis if the tumor is malignant.

Differential diagnoses for this condition in dogs include pigmented uveal cysts, ocular melanosis (Cairn Terriers), and pigmentary uveitis (Golden Retrievers).

In general, in canines, this is no big deal.

Uveal Melanoma with Extraocular Extension

Feline diffuse iris melanoma (FDIM) is the most common intraocular tumor type in cats. FDIM has a reported metastatic rate of around 60%, which sounds scary, but clinically most of these behave more like a benign process. Distant metastasis to liver, kidney, spleen, lungs, and central nervous system can occur. In young cats with rapid tumor growth, malignant/aggressive behavior is more likely.

The classic presentation is a focal flat hyperpigmented lesion within the iris that may or may not progress to a more diffuse hyperpigmentation with coalescing lesions. These lesions may start as amber to light brown and can progress to dark brown to black over time. Secondary uveitis, dyscoria and glaucoma may develop as the tumor progresses and are the signs to help clinicians discern between benign melanosis and malignant melanoma.

Enucleation with histopathology is the treatment of choice but in early cases, treatment with diode laser is becoming more popular. Staging before or after diagnosis may be recommended but success rates and survival with adjunctive chemotherapy or immunotherapy have not been reported.

The primary differential diagnosis for iris melanoma in feline patients is benign iris melanosis, characterized by variable hyperpigmentation within the iris tissue. This condition may also progress and may be a precursor to melanoma in some cases.

This is sort of SCARY but sometimes no big deal.

In conclusion:

Melanocytic ocular neoplasia in canine and feline patients should be diagnosed as malignant versus benign (melanocytoma) with histopathology and your recommendations for adjunctive treatment and concern for metastasis should be made only after knowing cytologically what you are dealing with in each case. In general, however, you can assume that MOST of these behave rather clinically benignly, and though distant metastasis has been reported for some of these tumor types, even malignant ocular melanomas rarely result in death. Staging and adjunctive treatment are recommended when malignant melanoma is confirmed with histopathologic evaluation.

References:

Andreani V, Guandalini A, D’Anna N, Giudice C, Corvi R, Di Girolamo N, Sapienza JS. The combined use of surgical debulking and diode laser photocoagulation for limbal melanoma treatment: a retrospective study of 21 dogs. Vet Ophthalmol. 2017 Mar;20(2):147-154.

Betton A, Healy LN, English RV, et al. Atypical limbal melanoma in a cat. J Vet Intern Med 1999;13(4):379-381.

Bussanich NM, Dolman PJ, Rootman J, et al. Canine uveal melanomas: series and literature review. JAAHA 1987;23(4):415-422.

Collins BK, Collier LL, Miller MA, et al: Biologic behavior and histologic characteristics of canine conjunctival melanoma. Prog Vet Comp Ophthalmol 1993;3(4):135-140.

Collinson PN, Peiffer RL. Clinical presentation, morphology, and behavior of primary choroidal melanomas in eight dogs. Prog Vet Comp Ophthalmol 1993;3(4):158-164.

Cook CS, Wilkie DA. Treatment of presumed iris melanoma in dogs by diode laser photocoagulation: 23 cases. Vet Ophthalmol 1999;2(4):217-225.

Day MJ, Lucke VM. Melanocytic neoplasia in the cat. J Small Anim Pract 1995;36:207-213.

Donaldson D, Sansom J, Scase T, Adams V, Mellersh C. Canine limbal melanoma: 30 cases (1992-2004). Part 1. Signalment, clinical and histological features and pedigree analysis. Vet Ophthalmol. 2006 Mar-Apr;9(2):115-9.

Donaldson D, Sansom J, Adams V. Canine limbal melanoma: 30 cases (1992-2004). Part 2. Treatment with lamellar resection and adjunctive strontium-90b plesiotherapy—efficacy and morbidity. Vet Ophthalmol 2006;9(3):179-185.

Finn, M. Krohne, S. Stiles, J. Ocular Melanocytic Neoplasia. Compendium. 2008. Jan;Vol 30, No 1

Giuliano EA, Chappell R, Fischer B, et al. A matched observational study of canine survival with primary intraocular melanocytic neoplasia. Vet Ophthalmol 1999;2:185-190.

Harling DE, Peiffer RL, Cook CS, et al. Feline limbal melanoma: four cases. JAAHA 1986;22(6):795-802.

Hendrix DVH: Diseases and surgery of the canine conjunctiva. In: Gelatt KN, ed. Veterinary Ophthalmology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1998:619-634.

Hyman JA, Koch SA, Wilcock BP. Canine choroidal melanoma with metastases. Vet Ophthalmol 2002;5(2):113-117.

Kalishman JB, Chappell R, Flood LA, et al. A matched observational study of survival in cats with enucleation due to diffuse iris melanoma. Vet Ophthalmol 1998;1(1):25-29.

Kayes D, Blacklock B. Feline Uveal Melanoma Review: Our Current Understanding and Recent Research Advances. Vet Sci. 2022 Jan 26;9(2):46.

Martin CL. Canine epibulbar melanomas and their management. JAAHA 1981;17(1):83-90.

McLaughlin SA, Whitley RD, Gilger BG, et al. Eyelid neoplasm in cats: a review of demographic data (1979-1990). JAAHA 1993;29(1):63-67.

Nasisse MP, Davidson MG, Olivero DK, et al. Neodymium:YAG laser treatment of primary canine intraocular tumors. Prog Vet Compar Ophthalmol 1993;3(4):152-157.

Payen, G., Estrada, M., Clerc, B. and Chahory, S. (2008), A case of conjunctival melanoma in a cat. Veterinary Ophthalmology, 11: 401-405.

Petersen-Jones SM. Ocular melanosis in cairn terriers. In: Riis RC, ed. Small Animal Ophthalmology Secrets. Philadelphia: Hanley & Belfus; 2002:105-109.

Roberts SM, Severin GA, Lavach JD. Prevalence and treatment of palpebral neoplasms in the dog: 200 cases (1975-1983). JAVMA 1986;189(10):1355-1359.

Ryan AM, Diters RW. Clinical and pathologic features of canine ocular melanomas. JAVMA 1984;184(1):60-67.

Sapienza JS, Simo FJ, Prades-Sapienza A. Golden retriever uveitis: 75 cases (1994-1999). Vet Ophthalmol 2000;3(4):241-246.

Sullivan TC, Nasisse MP, Davidson MG, et al. Photocoagulation of limbal melanoma in dogs and cats: 15 cases (1989-1993). JAVMA 208(6):891-894, 1996.

Wilcock BP, Peiffer RL. Morphology and behavior of primary ocular melanomas in 91 dogs. Vet Pathol 1986;23(4):418-424.